The following story is just one of countless situations in my life that really tested my faith. Not necessarily religious faith but faith in the conviction that my life has purpose. Faith that the path I have chosen to follow through life was the right one. Faith in myself. Faith in others. And yes, faith that there is a benevolent divine power to whom my life matters.

In 1982, the day after seeing Mad Max 2: Road Warrior in Vancouver, I put my BMW on a boat bound for Australia and a month later flew down and drove it around the country. Having been working as a writer, producer and director of business films for corporate and institutional clients in Canada, I was very keen on the Australian film industry at that time.

While motorbiking around the country, I read Maxwell Grant’s Inherit the Sun—the story of three generations of a pioneering family who, around the beginning of the last Century, settled in the Northern Territory— and thought it would make a great film or tv series. So, I headed to Adelaide, where the story begins, and up the Oodnadatta Track to become familiar with the landscape in which the novel plays out.

In the tiny oasis of William Creek, I ran into a bunch of young guys from Melbourne who had secured a contract from the South Australian Railway to tear up the old Ghan narrow gauge railway track between the towns of Marree and Oodnadatta and return the steel to the SAR. (The train got its nickname, The Ghan, from the fact that Afghans were originally brought to Australia with their camels to transport people and goods across the Outback.)

When they heard that I worked on a ballast gang repairing the tracks for the Canadian Pacific Railway as a student summer job in 1967, they invited me to join them for the remaining three weeks before the 1982 Christmas break.

So, there I was the very next day, swinging a spiking hammer knocking off rail fasteners in 45-degree Celsius (113°F) heat. Then climbing up as the excavator mounted on tracks that ran along the sides of the flat cars hauled 120-foot sections of track onto the decks of the flat cars. This usually resulted in the rails being twisted and wavy at which point, four of us would insert our heavy lining bars into holes in the rails and twist them straight before sliding them over flush with the previously loaded tracks.

We did this non-stop all day, piling the rails in stacks that were 4 or 5 rails high, not even stopping or lunch. As the rails piled higher, oil from the excavator made the surface more and slippery, a real potential hazard I later discovered the hard way when the lining bar I was pulling on to straighten a rail popped out. I went sliding backwards and did a perfect backwards swan dive off the top of the stack landing on my head and neck about 15 feet down as the train was on an embankment leading to one of the many bridges that span the dry river gulches along the route. Pumped full of adrenaline, I leaped back onto the rail car and straightened out the track single-handedly – a task that normally requires four men.

Our camp, so to speak, consisted of a couple of sleeper cars sitting beside the track with no running water, which meant we went to bed covered in grease from head to toe getting progressively blacker as the week proceeded until Sunday arrived and we could travel to the little pub/hotel at William Creek for our weekly shower.

By about the third day on the job, I was assigned to drive the huge twin diesel locomotives that hauled the long line of flat cars as we loaded them before taking the tracks down to Marree, unloading them and returning to the desert for more. I was given about two minutes of instruction before assuming control. “That’s forward. That’s back. Don’t give it too much welly or you’ll get sparks flying.”

At the end of those three weeks, I found myself in Marree looking for a way to get back to my motorbike which was stored at the little galvanized tin-covered William Creek Hotel.

No one was travelling up the Oodnadatta track at that time of the year, especially that year of the big drought with temperatures soaring around 45°C every day. Fortunately, I found a little section car abandoned beside the old railway station in Marree, carried out a few repairs to the broken frame and drove it the entire 200 kms of rail that remained, taking me to a point about 5 kms short of William Creek.

After walking in that withering heat for about 10 minutes, I was understandably pleased to see the hotel’s old Peugeot Station wagon coming in my direction. It was the hotel‘s hired hand who knew I was coming and just reckoned I should have reached the end of the line by about that time.

So, after going back to the section car and transferring all my gear into the car, we headed back to the hotel where I could shower up, rest and prepare for the journey ahead.

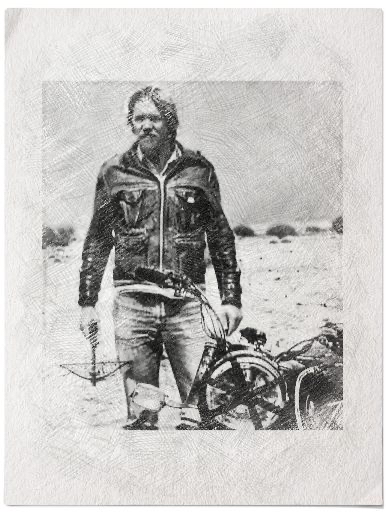

Two days later, Dec.24th, somewhere between the town of Oodnadatta and the Stuart Highway, as I pushed my bike as fast as I could hoping to get to Alice Springs for Christmas, I lost control on a rough section of the track, went over the handlebars, and smashed my unprotected head against the jagged rocks.

When I came to, and before I could even figure out who I was, where I was and which way I was going, I saw the bike on fire and, without a second thought, used what little drinking water I had to put out the flames.

It was only after the fire was extinguished and my mental faculties were restored, that I began to realize the seriousness of my situation. Here I was in the driest part of the driest state in the driest country during the worst drought in a century and I had just thrown away my water when, of course, sand would have been just as effective.

As that thought crossed my mind, I was relieved to feel drops of rain and looked up to thank the angelic cloud that had come to my rescue. To my surprise, the sky above me was bright blue, not a wisp of whiteness to be seen in any direction. Then, glancing back at the ground, I saw the rain I felt was bright red.

Quick inspection of my head in one of the shattered motorbike rearview mirrors revealed a gaping bone-exposing gash down the left side of my head from above the temple to behind the ear.

Locating one of two far-flung panier cases, I found my first aid kit and poured a small bottle of hydrogen peroxide into the hole in my head. As the contents frothed up and foamed, I wrapped a long roll of gauze around my head, then covered it with my stretchy knitted toque to hold everything in place.

I then turned my attention to finding a source of water somewhere in that vast desert landscape. Old Nat Geo documentaries suggested to me then it was possible to dig a hole under a bush and suck water up with a hollow reed. But not there, not that year. Everything was dry, bone dry. It was clear to me that by the next day, I would be dead from thirst and cooked like a Christmas turkey.

I knew that no one would find me, and I started to become angry. After all, it was thirteen years to the day since I had collapsed in Pakistan in a field, dying from typhoid, hepatitis, amoebic dysentery, and pneumonia. And having survived that occasion, 13 years later I still hadn’t discovered my true purpose in life.

As I cursed at God and swore that I wouldn’t even bother to write a goodbye note, something strange happened.

From out of nowhere, a gust of wind blew sand across my path as if I was being rebuked by the big man himself.

O ye of little faith!

As day turned into night, and I lay in the sand beside the track, the discomfort of thirst became overwhelming. I wanted to pull my tongue out and tear my skin off.

Drifting in and out of sleep, I had vivid dreams of canoeing in Canada on white water rapids and standing at the base of waterfalls soaking up the spray. I would see myself opening a fridge full of cold drinks.

A few times I awoke from a dream believing I had just figured out the solution to my dilemma. I could drink the water in my radiator or get the bike running by connecting the battery to the engine with a short piece of wire from a broken hanger, only to remember that the engine was air-cooled or realize that there was no way a short piece of wire could possibly replace that melted blob of a wiring harness.

At some time in the early morning, when that killer sun had returned to the sky, just before I opened my eyes to face my executioner, I heard a strange snorting sound. There was something, some kind of animal, out there in the desert with me.

Peeking cautiously through the slits of my eyes, I saw them. Brumbies-Australia’s wild horses. I was surrounded by a small herd of brumbies. In an instant, it dawned on me: Brumbies aren’t camels. There must be water out here somewhere.

Jumping up I grabbed my empty water bottle and headed off in the direction their tracks appeared to be coming from.

What if they’re going to the water, not coming from the water. I’m just taking myself further and further away from the track which that Aborigine in Oodnadatta warned me never to do. He said that’s the number one cause of people dying in the outback.

But deep down, I guess I reckoned that if they were on their way to the water, they wouldn’t be lingering in the bushes near the track. Thirst would have kept them moving towards the water. And sure enough, after trekking away from the track for a kilometer or so, I came over a small ridge and saw in the distance ahead of me a small pond.

Beside it was a small, broken-down caravan and a rusted windmill rising above that. This must be a spot where the drovers stopped with their stock in the days of cattle drives across the Outback. A thought reinforced by the sight of a bunch of scrub bulls standing between me and this life-saving pool.

Finding myself in a field full of bulls was a recurring childhood nightmare of mine but no childhood fear was going to stop me this time. Get out of my way, I growled in a low menacing voice as I marched straight towards them and the pond they seemed to be protecting.

As they moved aside, I spotted a couple of dingoes scurry along the water’s edge nervously slake their thirst then scamper away as I approached. The water itself was red and covered with green algae of some sort. Fitting colors for Christmas, I thought. It doesn’t look drinkable, but I don’t see any skeletons around. So, I filled my water bottle and started drinking and the instant the first molecules of H2O touched my parched palate, my whole body sprung back to life.

Without doubt. Best Christmas present ever. But there was more to come. After wallowing in the water till my whole body felt healed, I climbed out on the other side to explore the old caravan. To my amazement and delight, I discovered a small cache of food buried in the sand beside it. A tin of pears. Some condensed milk. A can of Spam. Plus, a well beaten aluminum pot and small gas cooker still containing fuel.

Just to be on the safe side, I boiled some water and filtered it back into my bottle. I tossed everything into a red plastic bucket lying nearby and set off for the track satisfied that with Christmas present number two, I can easily survive until help eventually arrives.

By the time I got back to the track, I sadly noticed that my brumby saviours were nowhere to be seen. Were they real or was I hallucinating? A fanciful thought but the presence of their hoofprints was all the proof I needed. Without them, I would have never ventured so far in search of water and Christmas 1982 would be looking very grim by now.

Settling into the sand, I prepared myself for the long wait when, suddenly, my eyes detected what appeared to be a rising plume of bulldust in the distance. Surely not. Not on Christmas day. The unmistakable sign of a vehicle in the Outback and it looks like it’s coming this way.

Sure enough, as I watched the billowing cloud of bull dust grow larger as it got closer, it wasn’t long before Christmas present number three came drifting around a bend and into sight. One of those tiny half-ton Toyota trucks or utes as the Aussies call them.

With a young man at the wheel and a young woman, presumably his wife, beside him, the little yellow ute raced towards me and then, to my bewilderment, drove right past. You’ve got to be kidding. What are they thinking?

Stunned, I just stood there frozen watching them barrel on down the track. Then, relief as brake lights flashed bright red against the dust covered tailgate and the tiny truck came to a sudden stop and started backing up. I guess it took a few seconds for them to put the pieces together. A mangled-looking motorbike on its side. A man covered in dried blood with a bandage wrapped around his head reminiscent of injured World War 1 soldiers in the trenches. Standing alone in the middle of nowhere on Christmas Day. He probably needs help.

With revs winding up to a high pitched screel, the tiny truck backed up like a rocket in reverse and braked hard when the side window reached the spot I was standing. Impassive curiosity on the faces of the occupants quickly evolved into shock and concern.

They had come from the Lambina Cattle Station about 50 kms from my crash site and, as I was soon to learn, were on that particular branch of the track completely by accident. When they left Lambina that morning, they intended to go in the opposite direction, straight to Oodnadatta. Instead, at the last minute, the man decided he wanted to check on something first and turned right. Still, they had a choice of following a few different forks in the track but just so happened to end up on the one that led them to me.

It was clear my Guardian Angels were working overtime. Highly commendable devotion to duty considering it was Christmas.

We managed to load the bike and my belongings into the miniature cargo box and, with the three of us crammed together in the tiny cab, carefully made our way back to the Lambina Station.

Around 4 o’clock that afternoon, the flying doctor landed in his twin engine Navajo, and after securely strapping me onto a gurney, flew 700 km south to Port Augusta via Coober Pedy for a brief fuel stop. Accompanying ne in the back of the plane was a nurse who spent the entire flight regurgitating her breakfast into a bag gripped tightly in both hands.

Before the stroke of midnight Christmas day, I found myself sitting comfortably in a bed in the Port Augusta General Hospital wearing crisp clean white hospital pajamas, my crude World War 1 dressing now replaced with a neatly applied sterile hospital bandage.

The gaping wound in my head was all stitched up after x-rays had revealed that damage to my skull was minimal. Their major concern now was to keep an eye out for any signs of post-concussion brain injury. But I wasn’t worried one bit as I greedily carved away at the delicious dinner I had been served.

Instead of ending Christmas 1982 as a sun-baked feast of human flesh for the Outback’s hungriest scavengers, it was me who was dining on the juicy well-cooked flesh of a proverbial Christmas bird, the words “Oh ye of little faith” still ringing loudly in my ears.

A footnote to this story. In Australia, businesses close for a lengthy Christmas and New Year’s Holiday, so buying parts to fix the bike was not possible. I also had no idea how I was going to get back to Lambina Cattle Station to fetch my bike.

So instead of worrying about it following discharge from the hospital, I made my way back to the Gold Coast to spend New Years Eve with a friend I met there back in October, then up to Cairns where I rented a jeep and drove up the Daintree Track to Cooktown through raging bushfires and surging rivers much to the dismay of the rental company.

I then flew to Alice Springs and made my way by bus to the South Australia border where I managed to hitch a ride with a jackeroo from the Granite Downs Cattle Station located on the Oodnadatta Track not far from the Stuart Highway that runs up the middle of the country. I was invited to stay at Granite Downs where they radioed the kind folks at Lambina and arranged to get my bike and belongings delivered a few days later.

The Granite Downs folks also got in touch with the SA Railway by radio and arranged for the train to Alice Springs to stop in the middle of nowhere to pick up me up. They then delivered me and my bike to the railway track where a crew of maintenance workers and their families resided in a cluster of cottages close to the railway line. One of them was kind enough to let me use his truck to load the bike on the train when it came which wouldn’t be until 3 in the morning. So, I was invited to join them forum impromptu “barbie” and beers.

Sometime after midnight, I staggered to the truck, parked it right beside the railway tracks and promptly passed out in the front seat until awoken by the conductor who helped me lift the bike onto the train. After returning the truck to the owner’s driveway, I ran back, jumped on the train and slept all the way to Alice Springs.

Inspired by moments in my life as described in this story, I have produced a song — Oh ye of little faith—with the help of an AI program which kindly provided me with a superb gospel choir to give my song just the right amount of vocal passion.